Related guidance:

Depression in adults: treatment and management NICE guideline (NG222 June 2022)

- For people with less severe depression who do not want treatment, or people who feel that their depressive symptoms are improving:

• discuss the presenting problem(s) and any underlying vulnerabilities and risk factors, as well as any concerns that the person may have

• make sure the person knows they can change their mind and how to seek help

• provide information about the nature and course of depression

• arrange a further assessment, normally within 2 to 4 weeks

• make contact (with repeated attempts if necessary), if the person does not attend follow-up appointments.

Depression in adults information leaflet (Royal College of Psychiatrists)

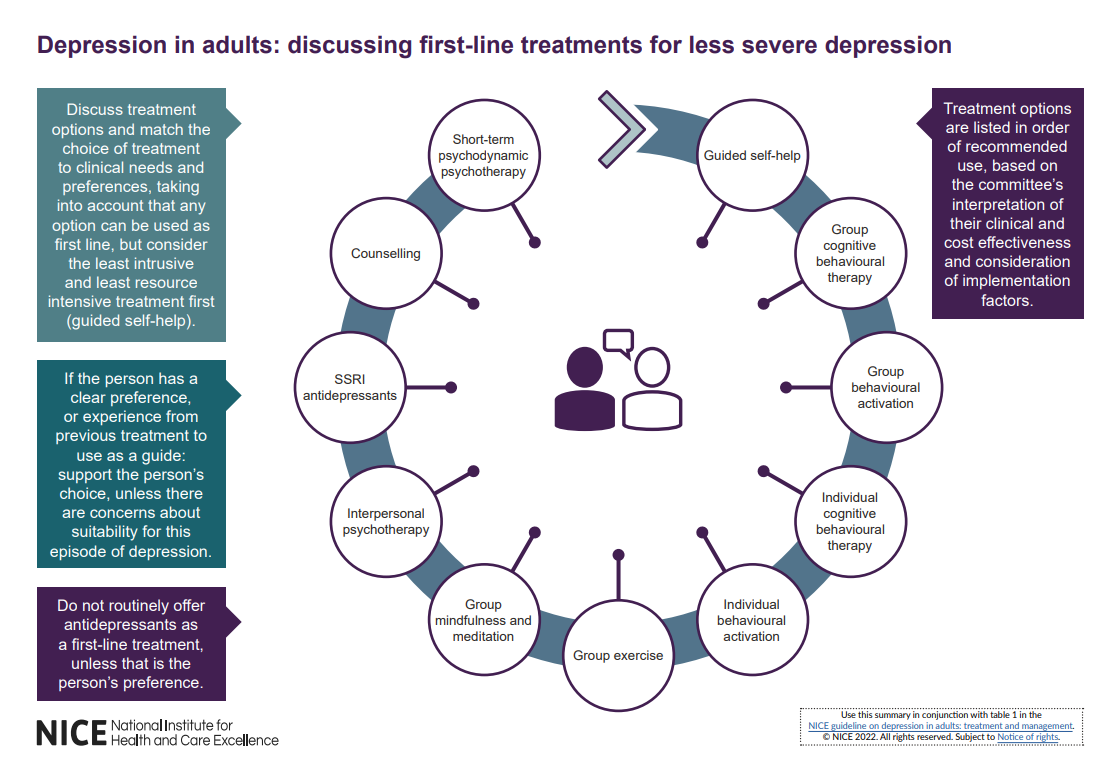

- Discuss treatment options with people with a new episode of less severe depression, and match their choice of treatment to their clinical needs and preferences:

• see visual summary below to guide and inform the conversation

• reach a shared decision on a treatment choice appropriate to the person’s clinical needs, taking into account their preferences

• recognise that people have a right to decline treatment. - Do not routinely offer antidepressant medication as first-line treatment for less severe depression, unless that is the person’s preference.

- When considering treatments for people with depression:

• carry out an assessment of need

• develop a treatment plan

• take into account any physical health problems

• take into account any coexisting mental health problems

• discuss what factors would make the person most likely to engage with treatment (including reviewing positive and negative experiences of previous treatment)

• take into account previous treatment history

• address any barriers to the delivery of treatments because of any disabilities, language or communication difficulties

• ensure regular liaison between healthcare professionals in specialist and non-specialist settings, if the person is receiving specialist support or treatment.

For people with depression who also have learning disabilities, see the NICE guideline on mental health problems in people with learning disabilities.

For people with depression who also have autism, see the NICE guideline on autism spectrum disorder.

For people with depression who also have dementia, see the NICE guideline on dementia.

For people with depression in pregnancy or the postnatal period, or who are breastfeeding, see the NICE guideline on antenatal and postnatal mental health.

For people with depression who are menopausal, see the NICE guideline on menopause.

For people with depression and physical health problems, see the NICE guideline on depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem.

- Match the choice of treatment to meet the needs and preferences of the person with depression. Use the least intrusive and most resource efficient treatment that is appropriate for their clinical needs, or one that has worked for them in the past.

Psychological and psychosocial interventions

- Inform people if there are waiting lists for a course of treatment and how long the wait is likely to be (for example, the NHS constitution advises that treatment should be started within 18 weeks). Keep in touch with people at regular intervals, ensure they are aware of how to access help if their condition worsens, ensure they are made aware of who they can contact about their progress on the waiting list. Consider providing self-help materials and addressing social support issues in the interim.

- Use psychological and psychosocial treatment manuals to guide the form, duration and ending of interventions.

- Consider using competence frameworks developed from treatment manual (s) for psychological and psychosocial interventions to support the effective training, delivery and supervision of interventions.

- All healthcare professionals delivering interventions for people with depression should:

• receive regular clinical supervision

• have their competence monitored and evaluated; this could include their supervisor reviewing video and audio recordings of their work (with patient consent). - When delivering psychological treatments for people with neurodevelopmental or learning disabilities, consider adapting the intervention as advised in the NICE guideline on mental health problems in people with learning disabilities.

- When people are nearing the end of a course of psychological treatment, discuss ways in which they can maintain the benefits of treatment and ensure their ongoing wellness.

Starting antidepressant medication

- When offering a person medication for the treatment of depression, discuss and agree a management plan with the person. Include:

• the reasons for offering medication

• the choices of medication (if a number of different antidepressants are suitable)

• the dose, and how the dose may need to be adjusted

• the benefits, covering what improvements the person would like to see in their life and how the medication may help

• the harms, covering both the possible side effects and withdrawal effects, including any side effects they would particularly like to avoid (for example, weight gain, sedation, effects on sexual function)

• any concerns they have about taking or stopping the medication. - Make sure they have written information to take away and to review that is appropriate for their needs.

- When prescribing antidepressant medication, ensure people have information about:

• how they may be affected when they first start taking antidepressant medication, and what these effects might be

• how long it takes to see an effect (usually, if the antidepressant medication is going to work, within 4 weeks)

• when their first review will be; this will usually be within 2 weeks to check their symptoms are improving and for side effects, or 1 week after starting antidepressant medication if a new prescription is for a person aged 18 to 25 years or if there is a particular concern for risk of suicide.

• the importance of following instructions on how to take antidepressant medication (for example, time of day, interactions with other medicines and alcohol)

• why regular monitoring is needed, and how often they will need to attend for review

• how they can self-monitor their symptoms, and how this may help them feel involved in their own recovery

• that treatment might need to be taken for at least 6 months after the remission of symptoms, but should be reviewed regularly

• how some side effects may persist throughout treatment

• withdrawal symptoms and how these withdrawal effects can be minimised.

For Interactions, see Appendix 1.

Antidepressants information leaflet (Royal College of Psychiatrists)

Stopping antidepressant medication

- Advise people taking antidepressant medication to talk with the person who prescribed their medication if they want to stop taking it. Explain that it is usually necessary to reduce the dose in stages over time (called ‘tapering’) but that most people stop antidepressants successfully.

- Advise people taking antidepressant medication that if they stop taking it abruptly, miss doses or do not take a full dose, they may have withdrawal symptoms. Also advise them that withdrawal symptoms do not affect everyone, and can vary in type and severity between individuals.

Symptoms may include:

• unsteadiness, vertigo or dizziness

• altered sensations (for example, electric shock sensations)

• altered feelings (for example, irritability, anxiety, low mood tearfulness, panic attacks, irrational fears, confusion, or very rarely suicidal thoughts)

• restlessness or agitation

• problems sleeping

• sweating

• abdominal symptoms (for example, nausea)

• palpitations, tiredness, headaches, and aches in joints and muscles. - Explain to people taking antidepressant medication that:

• withdrawal symptoms can be mild, may appear within a few days of reducing or stopping antidepressant medication, and usually go away within 1 to 2 weeks

• withdrawal can sometimes be more difficult, with symptoms lasting longer (in some cases several weeks, and occasionally several months)

• withdrawal symptoms can sometimes be severe, particularly if the antidepressant medication is stopped suddenly. - Recognise that people may have fears and concerns about stopping their antidepressant medication (for example, the withdrawal effects they may experience, or that their depression will return) and may need support to withdraw successfully, particularly if previous attempts have led to withdrawal symptoms or have not been successful. This could include:

• details of online or written resources that may be helpful

• increased support from a clinician or therapist (for example, regular check-in phone calls, seeing them more frequently, providing advice about sleep hygiene). - When stopping a person’s antidepressant medication:

• take into account the pharmacokinetic profile (for example, the half-life of the medication as antidepressants with a short half-life will need to be tapered more slowly) and the duration of treatment

• slowly reduce the dose to zero in a step-wise fashion, at each step prescribing a proportion of the previous dose (for example, 50% of previous dose)

• consider using smaller reductions (for example, 25%) as the dose becomes lower

• if, once very small doses have been reached, slow tapering cannot be achieved using tablets or capsules, consider using liquid preparations if available

• ensure the speed and duration of withdrawal is led by and agreed with the person taking the prescribed medication, ensuring that any withdrawal symptoms have resolved or are tolerable before making the next dose reduction

• take into account the broader clinical context such as the potential benefit of more rapid withdrawal if there are serious or intolerable side effects (for example, hyponatraemia or upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding)

• take into account that more rapid withdrawal may be appropriate when switching antidepressants

• recognise that withdrawal may take weeks or months to complete successfully. - Monitor and review people taking antidepressant medication while their dose is being reduced, both for withdrawal symptoms and the return of symptoms of depression. Base the frequency of monitoring on the person’s clinical and support needs.

- When reducing a person’s dose of antidepressant medication, be aware that:

• withdrawal symptoms can be experienced with a wide range of antidepressant medication (including tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], and monoamine oxidase inhibitors [MAOIs])

• some commonly used antidepressants such as paroxetine and venlafaxine, are more likely to be associated with withdrawal symptoms, so particular care is needed with them

• fluoxetine’s prolonged duration of action means that it can sometimes be safely stopped in the following way:

- in people taking 20 mg fluoxetine a day, a period of alternate day dosing can provide a suitable dose reduction

- in people taking higher doses (40 mg to 60 mg fluoxetine a day), use a gradual withdrawal schedule.

- allow 1 to 2 weeks to evaluate the effects of dose reduction before considering further dose reductions. - If a person has withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking antidepressant medication or reduce their dose, reassure them that they are not having a relapse of their depression. Explain that:

• these symptoms are common

• relapse does not usually happen as soon as you stop taking an antidepressant medication or lower the dose

• even if they start taking an antidepressant medication again or increase their dose, the withdrawal symptoms may take a few days to disappear. - If a person has mild withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking antidepressant medication:

• monitor their symptoms

• reassure them that such symptoms are common and usually time-limited

• advise them to contact the person who prescribed their medication if the symptoms do not improve, or if they get worse. - If a person has more severe withdrawal symptoms, consider restarting the original antidepressant medication at the previous dose, and then attempt dose reduction at a slower rate with smaller decrements after symptoms have resolved.

- When prescribing antidepressant medication for people with depression who are aged 18 to 25 years or are thought to be at increased risk of suicide:

• assess their mental state and mood before starting the prescription, ideally in person (or by video call or by telephone call if in-person assessment is not possible, or not preferred)

• be aware of the possible increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts, self-harm and suicide in the early stages of antidepressant treatment, and ensure that a risk management strategy is in place

• review them 1 week after starting the antidepressant medication or increasing the dose for suicidality (ideally in person, or by video call, or by telephone if these options are not possible or not preferred)

• review them again after this as often as needed, but no later than 4 weeks after the appointment at which the antidepressant was started

• base the frequency and method of ongoing review on their circumstances (for example, the availability of support, unstable housing, new life events such as bereavement, break-up of a relationship, loss of employment), and any changes in suicidal ideation or assessed risk of suicide. - Take into account toxicity in overdose when prescribing an antidepressant medication for people at significant risk of suicide. Do not routinely start treatment with TCAs, except lofepramine, as they are associated with the greatest risk in overdose.

Antidepressant medication for older people

- When prescribing antidepressant medication for older people:

• take into account the person’s general physical health, comorbidities and possible interactions with any other medicines they may be taking

• carefully monitor the person for side effects

• be alert to an increased risk of falls and fractures

• be alert to the risks of hyponatraemia (particularly in those with other risk factors for hyponatraemia, such as concomitant use of diuretics).

Use of lithium as augmentation

For lithium, see Bipolar disorder and mania.

- For people with depression taking lithium, assess weight, renal and thyroid function and calcium levels before treatment and then monitor at least every 6 months during treatment, or more often if there is evidence of significant renal impairment.

- For women of reproductive age, in particular if they are planning a pregnancy, discuss the risks and benefits of lithium, preconception planning and the need for additional monitoring.

- Monitor serum lithium levels 12 hours post dose, 1 week after starting treatment and 1 week after each dose change, and then weekly until levels are stable. Adjust the dose according to serum levels until the target level is reached.

• when the dose is stable, monitor every 3 months for the first year

• after the first year, measure plasma lithium levels every 6 months, or every 3 months for people in any of the following groups:

- older people

- people taking medicines that interact with lithium

- people who are at risk of impaired renal or thyroid function, raised calcium levels or other complications

- people who have poor symptom control

- people with poor adherence

- people whose last plasma lithium level was 0.8 mmol per litre or higher.

For Interactions, see Appendix 1.

- Determine the dose of lithium according to response and tolerability:

• plasma lithium levels should not exceed 1.0 mmol/L (therapeutic levels for augmentation of antidepressant medication are usually at or above 0.4 mmol/L; consider levels 0.4 to 0.6 mmol/L for older people aged 65 or above)

• do not start repeat prescriptions until lithium levels and renal function are stable

• take into account a person’s overall physical health when reviewing test results (including possible dehydration or infection)

• take into account any changes to concomitant medication (for example, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin 2 receptor blockers, diuretics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], or over-the-counter preparations) which may affect lithium levels, and seek specialist advice if necessary

• monitor at each review for signs of lithium toxicity, including diarrhoea, vomiting, coarse tremor, ataxia, confusion and convulsions

• seek specialist advice if there is uncertainty about the interpretation of any test results. - Manage lithium prescribing under shared care arrangements. If there are concerns about toxicity or side effects (for example, in older people or people with renal impairment), manage their lithium prescribing in

conjunction with specialist secondary care services. - Consider electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring in people taking lithium who have a high risk of, or existing, cardiovascular disease.

- Provide people taking lithium with information on how to do so safely, including the NHS lithium treatment pack.

- Only stop lithium in specialist mental health services, or with their advice.

- When stopping lithium, whenever possible reduce doses gradually over 1 to 3 months.

Use of oral antipsychotics as augmentation

For antipsychotics, see Psychoses and schizophrenia.

- Use of antipsychotics for the treatment of depression is off-label use for some antipsychotics.

- Before starting an antipsychotic, check the person’s baseline pulse and blood pressure, weight, nutritional status, diet, level of physical activity, fasting blood glucose or HbA1c and fasting lipids.

- Carry out monitoring as indicated in the summary of product characteristics for individual medicines, for people who take an antipsychotic for the treatment of their depression. This may include:

• monitoring full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests and prolactin

• monitoring their weight weekly for the first 6 weeks, then at 12 weeks, 1 year and annually

• monitoring their fasting blood glucose or HbA1c and fasting lipids at 12 weeks, 1 year, and then annually

• ECG monitoring (at baseline and when final dose is reached) for people with established cardiovascular disease or a specific cardiovascular risk (such as diagnosis of high blood pressure) and for those taking other medicines known to prolong the cardiac QT interval (for example, citalopram or escitalopram)

• at each review, monitoring for adverse effects, including extrapyramidal effects (for example, tremor, parkinsonism) and prolactin-related side effects (for example, sexual or menstrual disturbances) and reducing the dose if necessary

• being aware of any possible drug interactions which may increase the levels of some antipsychotics, and monitoring and adjusting doses if necessary

• if there is rapid or excessive weight gain, or abnormal lipid or blood glucose levels, investigating and managing as needed. - Manage antipsychotic prescribing under shared care arrangements.

- For people with depression who are taking an antipsychotic, consider at each review whether to continue the antipsychotic based on their current physical and mental health risks.

- Only stop antipsychotics in specialist mental health services, or with their advice. When stopping antipsychotics, reduce doses gradually over at least 4 weeks and in proportion to the length of treatment.

Use of St John’s Wort

- Although there is evidence that St John’s Wort may be of benefit in less severe depression, healthcare professionals should:

• advise people with depression of the different potencies of the preparations available and of the potential serious interactions of St John’s Wort with other drugs

• not prescribe or advise its use by people with depression because of uncertainty about appropriate doses, persistence of effect, variation in the nature of preparations and potential serious interactions with other drugs (including hormonal contraceptives, anticoagulants and anticonvulsants).

For Interactions, see Appendix 1.

- Dosulepin should not be prescribed.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (NICE CKS July 2023)

- Contraindications and cautions

- Adverse effects

- Drug interactions

Deprescribing of antidepressants for depression and anxiety (SPS)

- There is an association between the use of SSRIs and upper GI bleeds.

- The use of SSRIs with concomitant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), clopidogrel/low-dose aspirin, age of >80 or having a previous history of GI bleeding has been found to increase the risk of upper GI bleeding further.

- If an SSRI is required in a patient at high risk of an upper GI bleed, consider the use of a gastro-protective agent.

NHS Somerset recommends people prescribed long term NSAIDs, antiplatelet or an anticoagulant should be considered for co-prescribing with a PPI to reduce GI bleed risk.

For PPIs see Gastric acid disorders and ulceration.

Choosing an antidepressant to switch a person to (SPS February 2023)

Depression: treatment during pregnancy (SPS January 2022, updated April 2022)

Almost half of those on long-term antidepressants can stop without relapsing (NIHR March 2022)

Tricyclic antidepressants (STOPP criteria)

- In patients with dementia, narrow angle glaucoma, cardiac conduction abnormalities, prostatism, chronic constipation, recent falls, prior history of urinary retention or orthostatic hypotension (risk of worsening these conditions).

Drugs that predictably prolong the QTc interval (STOPP criteria)

- In patients with known with demonstrable QTc prolongation (to >450 msec in males and >470 msec in females), including quinolones, macrolides, ondansetron, citalopram (doses > 20 mg/day), escitalopram (doses >10 mg/day), tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, haloperidol, digoxin, class 1A antiarrhythmics, class III antiarrhythmics, tizanidine, phenothiazines, astemizole, mirabegron (risk of life threatening ventricular arrhythmias).

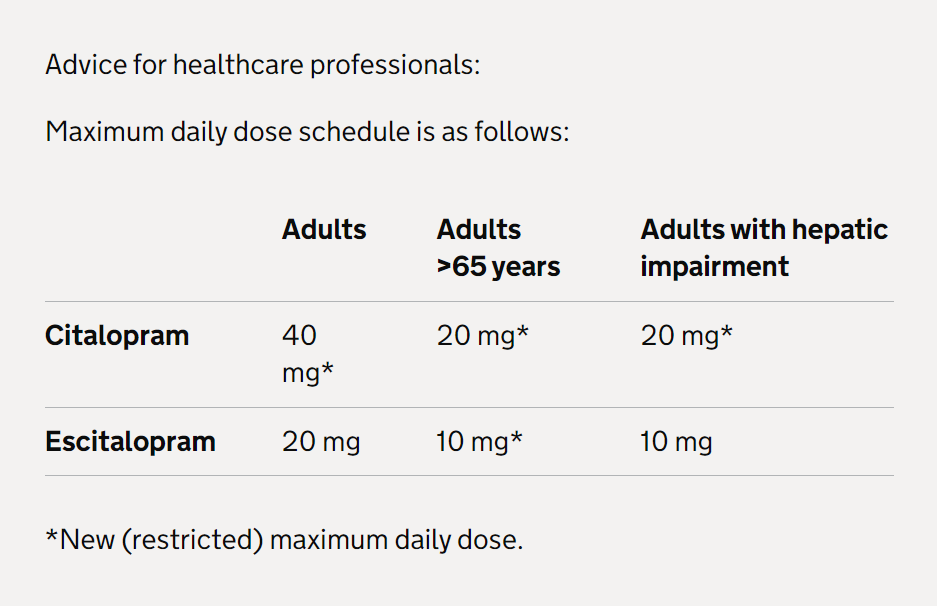

Citalopram and escitalopram: QT interval prolongation (MHRA December 2014)

- For both citalopram and escitalopram, elderly patients have a higher exposure due to age-related decline in metabolism and elimination. The maximum dose of both medicines has therefore been restricted in patients older than 65 years.

Therapeutic Area Formulary Choices Cost for 28

(unless otherwise stated)Rationale for decision / comments

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors Fluoxetine 20mg capsule: £1.24 (30) For major depression - Adult: Initially 20mg daily, dose is increased after 3-4 weeks if necessary up to 60mg per day. Usual maximum dose is 40mg daily for elderly patients.

The 10mg capsule is not cost effective, the 20mg dispersible tablet can be divided in to equal halves.

as Olena®

20mg dispersible tablet: £3.44

20mg/5ml oral solution sugar free: £12.95 (70ml)

Sertraline

50mg tablet: £1.04

For social anxiety disorder - Adult: Initially 25mg daily for 1 week, then increased to 50mg daily, then increased in steps of 50mg at intervals of at least 1 week if required, increase only if response is partial and if drug is tolerated, maximum 200mg per day.

For depressive illness - Adult: Initially 50mg daily, then increased in steps of 50mg at intervals of at least 1 week if required, maintenance 50mg daily, maximum 200mg per day.

100mg tablet: £1.22

New maximum daily dose restrictions (including in elderly patients), contraindications, and warnings. See MHRA (December 2014) for Citalopram and escitalopram: QT interval prolongation.

Citalopram

10mg tablet: £1.00 For depressive illness - Adult: 20mg once daily, increased to 40mg after 3-4 weeks if required. Elderly: 10-20mg once daily.

4 oral drops (8mg) is equivalent to 10mg tablet.

20mg tablet: £1.36

40mg tablet: £1.03

40mg/ml oral drops sugar free: £11.85 (15ml)

Escitalopram 5mg tablet: £1.06 For social anxiety disorder - Adult: Initially 10mg once daily for 2-4 weeks, dose to be adjusted after 2-4 weeks of treatment; usual dose 5-20mg daily.

Depressive illness - Adult: 10mg once daily; increased if necessary up to 20mg daily. Elderly: 5mg once daily; increased if necessary up to 10mg daily.

10mg tablet: £1.28

20mg tablet: £1.37

20mg/ml oral drops sugar free: £20.16 (15ml)

Serotonin and noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors Duloxetine

20mg gastro-resistant capsule: £2.09 For moderate to severe stress urinary incontinence - Adult (female): Initially 20mg twice daily for 2 weeks, this can minimise side effects, then increased to 40mg twice daily, the patient should be assessed for benefit and tolerability after 2-4 weeks.

40mg gastro-resistant capsule: £3.62 (56)

60mg gastro-resistant capsule: £2.68 For treatment for diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain - Adult (female): 60mg once daily up to a maximum dose of 120 mg per day administered in evenly divided doses.

Venlafaxine

Following our assessment of the latest safety evidence of venlafaxine, in particular relating to toxicity in overdose, we have updated prescribing advice. See MHRA (May 2006) for Updated prescribing advice for venlafaxine: Information for healthcare professionals.

37.5mg tablet: £3.74 (56) For major depression - Adult: Initially 37.5mg twice a day, then dose to be increased if necessary at intervals of at least 2 weeks up to 375mg daily. Faster dose titration may be necessary in some patients.

75mg tablet: £10.46 (56)

37.5mg modified-release capsule: £5.25 For major depression - Adult: Initially 75mg once a day, then dose to be increased if necessary at intervals of at least 2 weeks up to 375mg daily. Faster dose titration may be necessary in some patients.

75mg modified-release capsule: £3.29

150mg modified-release capsule: £4.72

225mg modified-release capsule: £13.71

37.5mg modified-release tablet: £6.60

75mg modified-release tablet: £2.60

150mg modified-release tablet: £3.90

225mg modified-release tablet: £33.60

Tetracyclic Mirtazapine 15mg tablet: £1.01

For major depression - Adult: Initially 15-30mg to be taken at bedtime for 2-4 weeks, then adjusted according to response to up to 45mg once daily.

30mg tablet: £0.99

45mg tablet: £1.24

15mg orodispersible tablet: £1.81 (30)

30mg orodispersible tablet: £1.85 (30)

45mg orodispersible tablet: £2.14 (30)

Tricyclic Lofepramine 70mg tablet: £12.11 (56) Depressive illness - Adult: 140-210mg daily in divided doses.

Lower incidence of side effects and less dangerous in overdose, but is infrequently associated with hepatic toxicity.

Amitriptyline 10mg tablet: £0.73 For abdominal pain or discomfort (in patients who have not responded to laxatives, loperamide, or antispasmodics)

Adult: Initially 5–10 mg daily, to be taken at night; increased in steps of 10 mg at least every 2 weeks as required; maximum 30 mg per day.

For neuropathic pain in adults (except trigeminal neuralgia) and migraine prophylaxis, initially 10-25mg daily, then increased, if tolerated in steps of 10-25mg every 3-7 days, usual dose 25-75mg daily, dose to be taken in the evening, doses above 100mg should be used with caution (doses above 75mg should be used with caution in the elderly and in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Amitriptyline is particularly dangerous in overdose and is not recommended for the treatment of depression.

25mg tablet: £0.75

50mg tablet: £0.95

50mg/5ml oral solution sugar free: £19.20 (150ml)

Other antidepressants Vortioxetine 5mg tablet: £27.72 For treating major depressive episodes that have failed to respond to two different antidepressants in the same episode.

Initially 5mg (elderly) to 10mg (adult) once daily, adjusted according to response to up to 20mg daily.

10mg tablet: £27.72

20mg tablet: £27.72