Related guidance:

Anaemia – iron deficiency (NICE CKS updated November 2021)

Anaemia – iron deficiency

- Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) is the most common form of anaemia seen in primary care in the UK. It is estimated to account for more than 57,000 emergency admissions to UK hospitals each year, costing the National Health Service (NHS) more than £55 million per annum.

- The cause of Iron deficiency anaemia is often multifactorial, and can be broadly be attributed to:

- Dietary deficiency — this is rarely a cause on its own. It takes about 8 years for a normal adult male to develop iron deficiency anaemia due to a poor diet, or malabsorption resulting in no iron intake.

- Malabsorption — for example due to coeliac disease, gastrectomy, or Helicobacter pylori infection.

- Other uncommon gastrointestinal causes include oesophagitis, schistosomiasis or hookworm, or inflammatory bowel disease.

- Increased loss — chronic blood loss, especially from the uterus or gastrointestinal tract (GI).

- In adult men and postmenopausal women, GI blood loss is the most common cause of iron deficiency anaemia. It can be caused by aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, colonic carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, benign gastric ulceration, or angiodysplasia.

- Menstruation is the most common cause of iron deficiency anaemia in premenopausal women.

- Other gynaecological causes include haemorrhage in childbirth.

- Increased requirement — physiological iron requirements are three times higher in pregnancy than they are in menstruating women, with increasing demand as pregnancy advances.

- Other causes — these include: blood donation, self-harm, haematuria (rare), nosebleeds (rare), medication.

- Diagnosis of anaemia caused by iron deficiency is made through history, examination and investigations.

- Take a detailed medical history, and ask about:

- Symptoms of anaemia.

- If the anaemia is severe, ask about specific cardiac symptoms (for example angina, palpitations, and ankle swelling).

- Diet (to identify poor iron intake).

- Drug history (for example the use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, clopidogrel, or corticosteroids).

- A family history of:

- Iron deficiency anaemia (which may indicate inherited disorders of iron absorption).

- Bleeding disorders and telangiectasia.

- Colorectal carcinoma.

- Haematological disorders (for example thalassaemia).

- Gastrointestinal disorders.

- A history of overt bleeding, heavy bruising or blood donation.

- A history of recent illness which might suggest underlying gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Menstrual history, pregnancy or breastfeeding (if appropriate).

- Travel history (increased risk of hookworm in travellers to the tropics).

- Weight loss.

- Symptoms of anaemia.

- Examine the person to look for signs of anaemia.

- Arrange necessary investigations.

- Consider other causes of anaemia.

- Before initiating treatment for anaemia, it is essential to determine which type is present. Iron salts may be harmful if given to people with anaemias other than those due to iron deficiency.

- Address the underlying causes as necessary (for example treat menorrhagia or stop nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, if possible).

- For more information, see the CKS topic on Menorrhagia.

- If dietary deficiency of iron is thought to be a contributory cause of iron deficiency anaemia, advise the person to maintain an adequate balanced intake of iron-rich foods (for example dark green vegetables, iron-fortified bread, meat, apricots, prunes, and raisins) and consider referral to a dietitian. Click here for The British Dietetic Association (BDA) Iron: Food Fact Sheet.

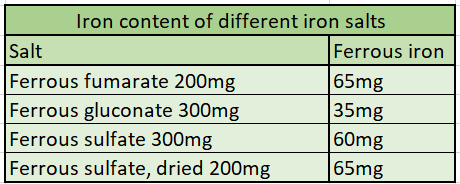

- Prescribe all people with iron deficiency anaemia one tablet once daily of oral ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate or ferrous gluconate — continue treatment for 3 months after iron deficiency is corrected to allow stores to be replenished.

- Monitor the person to ensure that there is an adequate response to iron treatment.

- Refer the person where appropriate.

- Options for people with significant intolerance to oral iron replacement therapy include alternate day dosing.

- Ferrous salts show only marginal differences between one another in efficiency of absorption of iron. Haemoglobin regeneration rate is little affected by the type of salt used provided sufficient iron is given, and in most people the speed of response is not critical.

- Modified-release preparations of iron are licensed for once-daily dosage, but have no therapeutic advantage and should not be used.

- NHS Somerset classify Ferric maltol as a green drug as per traffic light guidance with an off licensed dose of once daily for patients who have exhausted strategies to reduce side effects from lower cost iron preparations including: taking supplements with or after food (foods such as eggs and tea, as well as drugs such as antacids and tetracyclines reduce absorption; ascorbic acid/vitamin C increases absorption), reducing the dose frequency to once a day (now the recommended starting frequency for conventional supplements) or one tablet on alternate days and changing preparation to one containing a lower iron content.

Anaemia – B12 and folate deficiency (NICE CKS updated March 2022)

Anaemia – B12 and folate deficiency

- Diagnosis of anaemia caused by vitamin B12 or folate deficiency is made through history, examination and investigations.

- Take a detailed medical history, and ask about:

- Examine the person to look for signs of anaemia, B12 and folate deficiency.

- Arrange necessary investigations.

- Consider non-megaloblastic causes of macrocytosis.

- Determine whether there is an underlying cause for the vitamin B12 or folate deficiency — this may require specialist referral.

- If folate levels are low, assess dietary folic acid intake, and if history suggests malabsorption, check for coeliac disease by testing for antiendomysial or antitransglutaminase antibodies (depending on the local laboratory).

- The main cause of folate malabsorption is gluten-induced enteropathy.

- If cobalamin levels are low, check for serum anti-intrinsic factor antibodies.

- Also test people with strong clinical features of B12 deficiency, such as megaloblastic anaemia or subacute combined degeneration of the cord, despite a normal cobalamin level.

- If folate levels are low, assess dietary folic acid intake, and if history suggests malabsorption, check for coeliac disease by testing for antiendomysial or antitransglutaminase antibodies (depending on the local laboratory).

- Determine whether the person has experienced complications of anaemia, vitamin B12 or folate deficiency.

- Refer or treat the person where appropriate depending on the suspected cause.

Vitamin B12 deficiency anaemia

- For people with neurological involvement

- Seek urgent specialist advice from a neurologist and/or haematologist.

- Ideally, management should be guided by a specialist, but if specialist advice is not immediately available, consider the following:

- Initially administer hydroxocobalamin 1 mg intramuscularly on alternate days until there is no further improvement, then administer hydroxocobalamin 1 mg intramuscularly every 2 months.

- For people with no neurological involvement

- Initially administer hydroxocobalamin 1 mg intramuscularly three times a week for 2 weeks.

- The maintenance dose depends on whether the deficiency is diet related or not. For people with B12 deficiency that is:

- Not thought to be diet related — administer hydroxocobalamin 1 mg intramuscularly every 2–3 months for life.

- Thought to be diet related — adminiter twice-yearly hydroxocobalamin 1 mg injection.

- In vegans, treatment may need to be life-long, whereas in other people with dietary deficiency replacement treatment can be stopped once the vitamin B12 levels have been corrected and the diet has improved.

- For non-dietary vitamin B12 deficiency, oral cyanocobalamin can be offered at a dose of 1 mg per day until regular IM hydroxocobalamin can be resumed.

- If however a clinical decision is made to keep the patient on oral cyanocobalamin then NHS Somerest recommend consideration of 1mg per day dose (No clinical concerns exist in moving to this higher dose) as this would rule out the possibility of sub optimal dosing – ‘care must be taken if low dose oral cyanacobalamin is used as this risks suboptimal treatment of latent and emerging pernicious anaemia with possible inadequate treatment of neurological features’.

-

- Give dietary advice about foods that are a good source of vitamin B12 — good sources of vitamin B12 include:

- Eggs.

- Foods which have been fortified with vitamin B12 (for example some soy products, and some breakfast cereals and breads) are good alternative sources to meat, eggs, and dairy products.

- Meat.

- Milk and other dairy products.

- Salmon and cod.

- Give dietary advice about foods that are a good source of vitamin B12 — good sources of vitamin B12 include:

The British Dietetic Association (BDA) Vegetarian, vegan and plant-based diet: Food Fact Sheet

Folate deficiency anaemia

- Prescribe oral folic acid 5 mg daily — in most people, treatment will be required for 4 months.

- However, folic acid may need to be taken for longer (sometimes for life) if the underlying cause of deficiency is persistent.

- Check vitamin B12 levels in all people before starting folic acid — treatment can improve wellbeing, mask underlying B12 deficiency, and allow neurological disease to develop.

- Give dietary advice about foods that are a good source of folic acid — good sources of folate include:

- Asparagus.

- Broccoli.

- Brown rice.

- Brussels sprouts.

- Chickpeas.

- Peas.

- Click here for The British Dietetic Association (BDA) Folic Acid: Food Fact Sheet

- For information on folic acid supplementation in pregnancy, see the CKS topic on Pre-conception – advice and management.

Vitamin B12 deficiency: treatment during pregnancy (SPS April 2022)

General Haematology; Advice on B12 supplements (BSH updated May 2020)

See NHS Somerset Medicines used in pregnancy for Folic acid guidance when planning pregnancy

| Therapeutic Area | Formulary Choices | Cost for 28 (unless otherwise stated) | Rationale for decision / comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron | Ferrous fumarate | 210mg tablet: £3.99 (84) | For iron deficiency anaemia prescribe once daily or alternate days in significant intolerance. |

| 322mg tablet: £1.00 | |||

| Ferrous fumarate as Galfer Syrup® | 140mg/5ml solution: £5.33 (300ml) Sugar free. |

||

| Ferrous gluconate | 300mg tablet: £0.93 | ||

| Ferrous sulfate | 200mg tablet: £1.57 | ||

| Ferric maltol as Feraccru® | 30mg capsule: £47.60 (56) | For iron deficiency anaemia prescribe once daily as per Traffic light guidance. | |

| Folates | Folic acid | 400mcg tablet: £3.52 (90) | For folate deficiency anaemia prescribe folic acid 5 mg daily. |

| 5mg tablet: £0.84 | |||

| Vitamin B group | Hydroxocobalamin (Vitamin B12) | 1mg/1ml solution for injection ampoule: £7.30 (5) | For maintenance administer 1mg by intramuscular injection every two to three months. |

| Cyanocobalamin (Vitamin B12) as Orobalin® | 1mg tablet: £9.99 (30) |